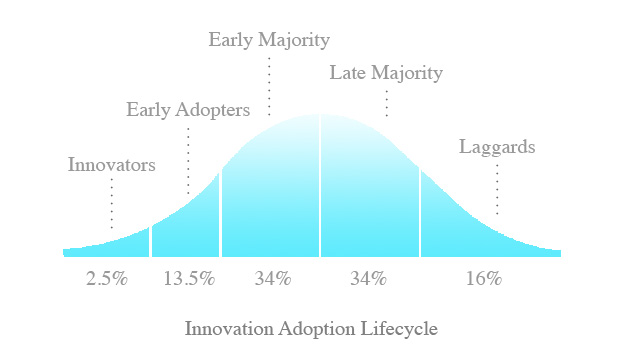

You may be familiar with the theory of ‘diffusion of innovations’. It was developed by Everett Rogers in 1968 to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread through cultures. In simple terms, it’s a scientific and mathematical answer to questions like, “Why the hell would someone queue for 14 days in freezing rain to buy the new iPhone on the first day, when they can waltz in and buy it off the shelf the following week?”. The answer is easy: they want to be the first. So what is so great, or so important, about being first? Sure, there is always that superficial ego-boost attached to telling people, “I had it first!” but the mileage in this reasoning is pretty limited. The real benefits actually have a much bigger scope by comparison.

The leading minority

According to Rogers’ theory (depicted in the chart above), innovations must be widely adopted in order to self-sustain. The categories of adopters are: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards. The early majority and late majority (representing 68% of the population) won’t be inclined to try anything new until someone (namely an ‘early adopter’) has tried it first. Therefore, without those first 16%, the cycle wouldn’t exist and advancement would be impossible. Innovators and early adopters believe in challenging the status quo, and by doing so they enable ideas that shape our industry in important ways.

Tough crowd…

The design industry experienced an unprecedented leap in the 20th century. Through the Bauhaus and in Modernism, people dared to innovate, even at the risk of facing total failure. We tend to forget the struggles endured by designers such as Ray and Charles Eames, who sneaked materials into their LA apartment late at night to produce the world’s first moulded-plywood chair in the mid-1940s. Or what about Verner Panton? We all know him as the man who designed the first injection-moulded chair produced by Vitra in 1968, but hardly anyone speaks about the fact that Mies van der Rohe had experimented with injection moulding much earlier, in the 1930s. This invention, which is commonplace today, was initially met with doubt and rejection and, as such, took 30 years to emerge. However, with persistence, a giant leap forward in chair-making was achieved.

Tall order

Today, innovation carries a critical social responsibility: preparing the world for future generations through responsible, resourceful and sustainable practices. By 2030, it’s estimated the world’s middle class will number five billion people (from the current two billion), in a world where resources are already scarce. By 2040, the entire Amazon will be wiped out, taking with it 19% of the world’s oxygen and 25% of the 3000 plants from which cancer treatments are derived. Innovation is no longer a nice ‘to do’ but a ‘must do’.

In 2012, I launched 19 greek street as a space for experimentation and advancement in design. Now it is home to nine eclectic design collections that are sustainable, finely crafted and aesthetically pleasing. While our concept has been extremely well received, I am still surprised at how resistant many people are to change.

I appreciate that some of the methods we represent appear a little far-fetched. For instance, creating a design (Mathias Bengtsson’s Growth Chair) using a sophisticated bio-mimicry process by which a seed is planted in a computer-generated 3D environment is not ordinary. But let’s not forget that there was a time where simple processes such as injection moulding seemed ridiculous and improbable.

Where do you stand?

You don’t have to share 19 greek street’s philosophy to be a good designer, but when faced with a choice between ‘traditional methods’ and ‘pushing the boundaries’, I urge you to re-evaluate your stance with regard to the aforementioned ‘diffusion of innovations’. When you opt for the status quo, you are implying that design has reached its full potential. Choosing experimentation means you are choosing to be part of a progressive minority, and a leader of important change in the world.